When the psychoanalyst Carl Jung was challenging the philosophy of Sigmund Freud, he needed complete focus.

Freud had become the leading voice in psychiatry, and Jung supported him early in his career, because of their shared interest in the subconscious mind. But as Jung grew older, and saw more patients in his Zurich office, he found flaws with Freud’s approach that did not align with what he saw in his patients.

When Jung publicly challenged the Oedipus complex, a cornerstone of Freud’s psychiatric theory, the two men became antagonists, writing papers against one another.

(It reminds me of the description of a ‘rap battle’ – two dudes sitting alone in a room, writing poems about one another.)

Having a brilliant opponent is difficult, especially when you are distracted by seeing clients all the time.

In order to focus his arguments against Freud, Jung spent a couple of days every week in a secluded forest retreat. He spent his time there writing, reading, and thinking.

art by Midjourney

Jung also spent a couple of days every week in Zurich, seeing patients and gathering experience that he could use in his writing.

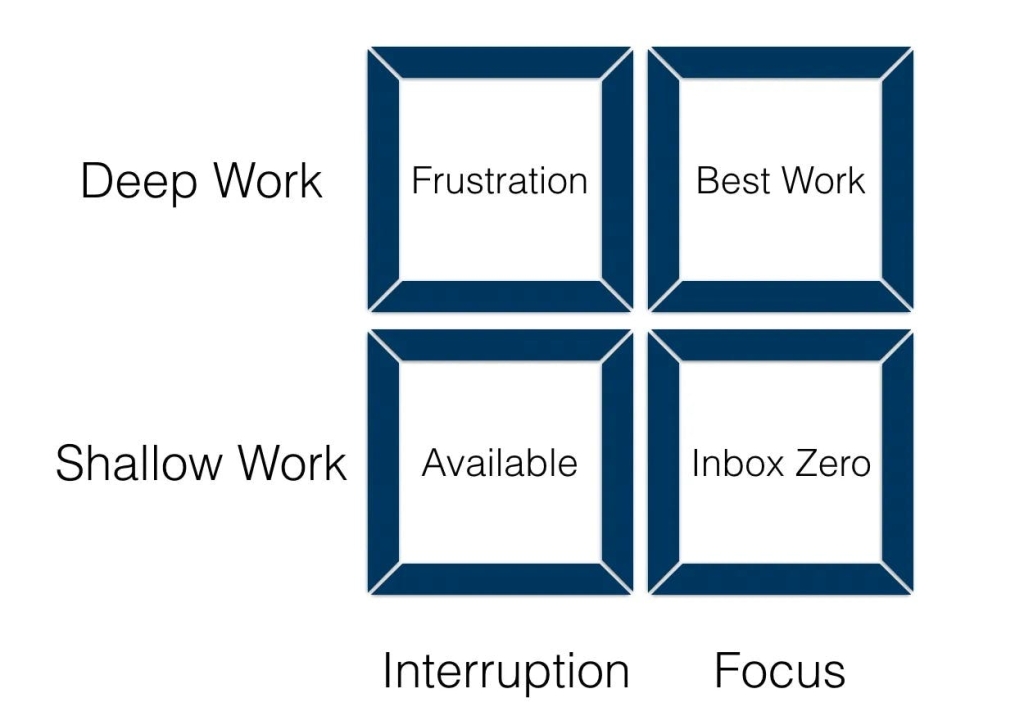

By separating deep work from shallow work, he was able to preserve his attention for when he needed it most.

Deep work requires deeper focus.

According to a study by time-tracking app Rescue Time, after analyzing the time tracking data of more than 50,000 users, they found that most professionals only spend 38% of their workday on their core skills.

We are constantly interrupted by urgent, non-important tasks, which derail us from the deeper work that requires greater focus. This is an inefficient use of our attention, because you change your mind when you change your work.

In 2019 the German professor Magnus Liebherr published a study in the journal Frontiers of Psychology that measured the switching costs between different types of work. This quantifiably measured the lack of efficiency when we change our attention. In an experiment designed to test attentional demands and measure switching costs, he measured both selective and divided attention.

Selective attention is when you are focused on one task, with one input. Divided attention is when you have multiple inputs, or are working on multiple tasks. The switching costs, he found, “significantly increase in selective but not in divided attention.”

What does this mean? When you are involved in shallow work, this study demonstrates, interruptions do not decrease your efficiency nearly as much as when you are focused on deeper work.

We all need time to engage with our most difficult problems, and we also need to be available to interruptions. Dedicating portions of your day to each type of attention will allow you to be available to your team or your family, while earning you the right to hunker down and stay focused when you need.

Earn the time for Deep Work by being available for Shallow Work.

Interruptions can be easy, and even welcome, for shallow work. Think of a university professor, who teaches classes, writes books, and advises students one-on-one.

If a student comes by a professor’s office while they are teaching a class, they will not get the professor one-on-one. If they try to interrupt the professor in the middle of a writing sprint, they will be told to get lost. Because a professor has Open Office Hours, specific periods of time when they are open to interruption, they earn the right of seclusion.

You can bother a professor about anything you want during Open Office Hours. If nobody shows up during that time, the professor might check emails, or tidy their desk, or do some form of shallow work that is easy to interrupt. Having this dedicated time for shallow work will give them the right to tell a student to scram outside of those hours.

I have been working from home for more than a decade, and we homeschool our children. When the kids are hungry, or having a fight that needs to be adjudicated, or they just made a big mess, they go to their mom. When I am in my office, I am often delivering virtual keynotes, or in a deep conversation with a coaching client, or wrestling with creative technology that requires deep focus. They have learned that if they disturb me during my working hours, they will not get my attention.

Sometimes my wife has things to do. She might have a doctor’s appointment, or go out to the grocery store, or meet a friend at a cafe. During those times, I bring my laptop out to the kitchen table and do some shallow work.

My kids know that if I am at the kitchen table, they are free to interrupt me. So I make sure that I don’t try to do any deep work out there, where I can be interrupted. When my laptop is on the kitchen table, I write short email responses, but I don’t edit long manuscripts.

- Shallow work is for responding to others, when you are open to interruption.

- Deep work is for making decisions, and staying focused on complicated projects.

One is not better than the other. It’s like ketchup and chocolate – two great tastes that don’t taste great together.

“If you’re busy, you’re doing something wrong.” – Cal Newport

We wear busy-ness as a badge of honor. But being ‘busy’ demonstrates a lack of planning, and an inability to separate deep from shallow work.

Deep work, as defined by Cal Newport in his book of the same name, is characterized as “Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.”

Shallow work, he says, consists of “Non-cognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.”

Parenting is shallow work. You can expect to be interrupted, you stay open to the goals of others, and you spend more of your time in responding.

Deep work, however, requires focus. The goals in deep work are your own, and not the goals of others. The main activity in deep work is not responding, it is deciding.

Separate time for deep & shallow work every day.

Stay focused and quiet some of the time, but not all of the time. Do your shallow work when you can be open to interruption, and preserve your attention when doing your deeper work. Focus quietly on hard things, and don’t let yourself be interrupted unless what you’re doing is easy.

What time of day is best for your Deep Work? When is the right time for your Shallow Work? Do these happen in different places? What activities are best for each one?

Write two lists, with the words ‘Shallow Work’ on the top of one and ‘Deep Work’ at the top of the other. Get it out of your mind, and add to it over the next few days.

This is shallow work, writing things down. Deciding what to do, when and where to do it – that is deep work, and it requires deeper thinking.

This article is an excerpt from my next book, Playful Productivity. To get notified when it’s ready, sign up for the wait list here.

Leave A Comment