When I spent a year attending the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre, we spent a lot of time working hard on our ability to play.

Class of 2001

The program was intense. Dozens of students from all around the world came together in a small town in Northern California, high up in the Redwood forest, and met in a renovated Odd Fellow’s Hall. (It’s sort of like a Masonic Hall, but for weirdos.)

We studied and practiced and rehearsed and performed for hours every day. The pace of the curriculum was grueling, and we studied Physical Theatre, Melodrama, Pantomime, Clown, and Commedia dell’Arte, an ancient 15th-century form of Italian street theatre.

That’s me on the left on the unicycle

Our teachers in modern dance, yoga, acrobatics, and voice would give us training exercises that alternated repetitions with exploratory play.

First we would drill new skills, and then we would improvise using those skills as an ensemble. Every Friday evening we collected our experiments into a performance called Bits & Pieces. We gathered together in groups of 2-5 every week, to create a short performance that showcased what we had learned recently.

Every morning, warm-ups began at 8:30. We had thirty minutes of stretching and socializing before classes started at 9. This early morning warm-up gave a buffer to students who were late or overslept – the physical training in this program required a lot of physical self-care, and we were often recovering from injuries or sore muscles. The daily morning warm-up time gave us a moment to check in with our bodies, explore what we needed, and give ourselves the stretches and attention we needed to prepare for the day.

Sometimes we would gather for spontaneous collective warm-ups. Tim would scream ‘Push-ups!’ and everyone who wanted to join would participate in his 5 sets of 20 push-ups, to reach a total of 100 for the morning. Wini had a Tae-Bo phase. Duckie juggled five balls and tried to fit in a sixth. And Bob did handstands.

Every morning, Bob would spend ten to fifteen minutes upside down. His balance on his hands was just as casually perfect as any normal human standing on their feet. He could shift his weight from palm to palm, carry on conversations, and even walk around.

Photos by Jenny the Juggler

When I asked him about his dedication to handstands, I was still trying to balance upright without a wall for more than five seconds. He shrugged – which looked really weird in a handstand, like he was squatting from his hips without his knees – and he told me, ‘All it takes is practice.’

His handstands used to be great, he told me, but had fallen off the past few years. He took the opportunity of being enrolled in Dell’Arte to gain excellent proficiency in handstands, but he didn’t see the time spent as work. His handstands were his play. Every minute he spent upside-down gave him greater confidence and stability in every future handstand, because his play was a practice.

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” – Will Durant

The road to mastery is paved with repetitions.

When our mime teacher demonstrated the first movement of the Corporeal Scales, and we all cocked our head to the side, curious and precise.

Rotating your head, and only your head, 45 degrees to the right without moving your spine, was the first movement in the scales of pantomime. We drilled this movement dozens of times, watching our reflections in the studio mirror as we stood in Le Tour Eiffel, an ‘A’ stance.

Daniel Stein was of the Decroux school, even though Dell’Arte was nominally a Le Coq school according to its pedagogy. Having lived in France for decades as a professional mime, serving as the personal translator for Etienne Decroux (author of the seminal work Words On Mime) the school director of Dell’Arte gave us gossipy insights into the feuds in French mime that had been simmering for decades.

The exercise he was teaching us, the Corporeal Scales, was an exercise common to both schools. These precise movements gave the performer a vocabulary to use in physical theatre. Just as the scales of a musical instrument are practiced to master the notes, the scales of the body are practiced to master corporeal movement.

We moved on to the second ‘note’ in the scale, rotating the neck from C7, the very bottom of the neck and the top of the shoulders. Dozens of alternating movements to the right, and then to the left, were practiced before moving lower in the spine – from the centre of the chest, to the navel, to the hips, to the feet, we would bend our bodies with obsessively precise control. We made our bodies into metronomes.

Starting mime class on Tuesday mornings with scales gave us two things: 1. an acquaintance with the subtle imperfections of our own movements, and 2. a limbering of our joints that enabled us to explore intentionally with our bodies for the next two hours.

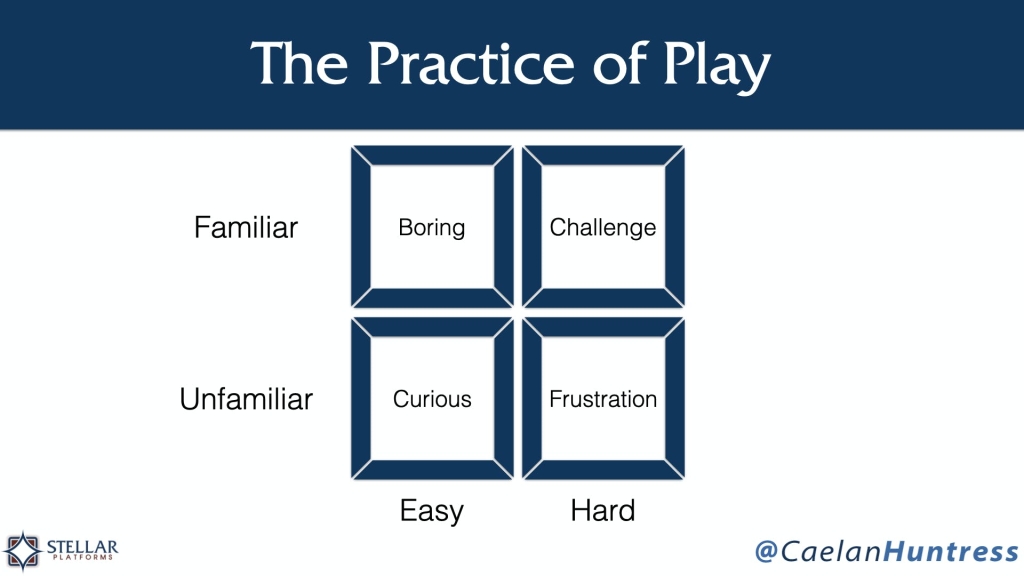

That flexibility of movement in improvisation was the true goal. You get better at playing if you practice the scales. The boring, easy practice gives you greater capacity to handle challenge.

Starting with scales gives you mastery of your play.

My wife was fortunate enough to meet Yo-Yo Ma, the acclaimed cellist. The private workshop on an empty stage was a rare opportunity to have her performance examined and critiqued by one of the greatest cellists in the world. She was allowed to play his instrument, which was centuries old. Nervously, Johanna played a piece for the great cellist, and was quickly stopped.

‘Play the first note of that piece,’ he asked of her, ‘and play that note the very best you can.’

She played the first note of the piece, intentionally, repeatedly, to discover the best way that note could ever be played.

This granular focus onto a single detail can seem obsessive, to those who are not well acquainted with play. Improvisationally, play happens in the moment, and the playful experience cannot be practiced in advance. But paradoxically, it is the disciplined focus on the tiniest of details that allows you to improve your performance in the moments when there is no discipline.

Meeting with other musicians for a jam session is a communal playful experience. Everyone gets together, tunes to the same note, fiddles with a few riffs, and then someone sets a beat, or gets loud, and everyone else joins in to create something new and unusual and interesting.

This gestational phase of play cannot be practiced, it can only experienced. It’s like when basketball players are milling about on a court, and everyone has stretched and is now looking at one another expectantly. Somebody tosses the ball in and everyone begins the game. The play of this particular game is unique, and can never be replicated again; but it is built on the precise replications of many movements that were practiced thousands of times in advance.

Bouncing a ball from hand to hand is called ‘dribbling,’ and it is one of the scales in basketball. You can practice dribbling endlessly, or shooting 3-pointers, or bouncing a ball behind your back, or through your legs – all of these scales improve your play, when you enter into the experience.

Drilling the basics gives you the freedom to improvise.

If you are still trying to catch the ball as it bounces from one hand to another, you won’t have the mental or physical liberty to dodge around an opponent. If you are still trying to hit the E note with your pinky finger without making a squeak, your music will always sound its flaws. By practicing scales, you gain the ability to thoughtlessly use your skills in service of your exploration.

“Practices are what do – or don’t – accomplish goals.” – Mike Rayburn

Play is a practice, and practice is how you improve. Your playfulness will increase with the frequency and depth of your play.

Your ability to play can atrophy

When we don’t take time to play, it can feel unfamiliar, strange, and uncomfortable to try it again. They say you never forget how to ride a bike, and after years you can hop on and ride again. But can you enjoy it, without practice?

Would you be able to improvise and explore on your first bike ride in twenty years? Or would you need a few sessions to re-familiarize yourself with the pedals, the balance, and the sense of momentum and speed before you could pop a wheelie?

Everything is unfamiliar when it’s new. Whether you play an instrument, a game, or a role, practicing what you play gives you expertise. Losing a game, or playing the wrong note, can make you better at playing (as long as you practice what you’ve learned).

Ever since my days as an acrobat in the circus, I have diligently practiced my play. Developing the physique for handstands and backflips takes a lot of practice – drilling movements, holding positions, stretching and strengthening.

There is an online course for developing Gold Medal Bodies (that’s their brand name). They offer tutorials on the drills and exercises you need to practice to develop an elite-level physique using bodyweight training. One of their maxims is, “Practice happens at the edge of your ability; Play happens at the core of your competence.”

In order to play, you need to practice something so deeply that you don’t need to try for it anymore. Memorizing a song requires repetitive practice. You sing or play the notes repeatedly, with diligent focus, until you can remove your focus and play it anyway.

You will improve your proficiency with practice. What would improve your life if you practiced doing it every day? If you play your life like a game or an instrument, you can practice becoming what you want to be.

Leave A Comment