In every story, there are three characters: the hero, the villain, and the victim.

A century ago, American film was born out of the vaudeville scene. The main storytelling medium at the time was melodrama, when the characters were almost comically basic.

Think of the mustachio-twirling villain, tying a damsel in distress to the train tracks, being thwarted by a gun-toting hero, and you have all the basics you need to tell a compelling story: setting, conflict, and characters.

Melodrama worked for so long because it was so simple. You could look at the characters and instantly identify the hero and the villain.

A couple of months ago, I wrote about What Most Marketing Gets Wrong, and how experts and entrepreneurs often mistake themselves for the hero in the story of their business. Spoiler alert, if you didn’t read that article: you are not the hero. Your customer is the hero, and you are the wise mentor who helps them on their quest.

So this begs the question:

Who is the villain that opposes your customer?

For Netflix, the villain is sleep. The Sandman is the obstacle that would keep a Netflix subscriber from consuming more content. Domino’s Pizza had The Noid a few decades ago – ‘Avoid The Noid’ was their unwieldy catchphrase, and The Noid meant the stale pizza that took too long to be delivered. Mucinex had a popular villain ten years ago, Mr. Mucus. These villains were used by brands to tell a story, with the customer as the hero.

We all know Marvel’s greatest villain, Thanos. And DC’s greatest villain, of course, is Rotten Tomatoes. 😂

Identifying a villain for your brand story can be very helpful. It gives you something to push off of. You can write stories about the battle between the hero (your customer) and the villain (their opposing force). A villain for your customer can be a person, or a condition, or a force of nature.

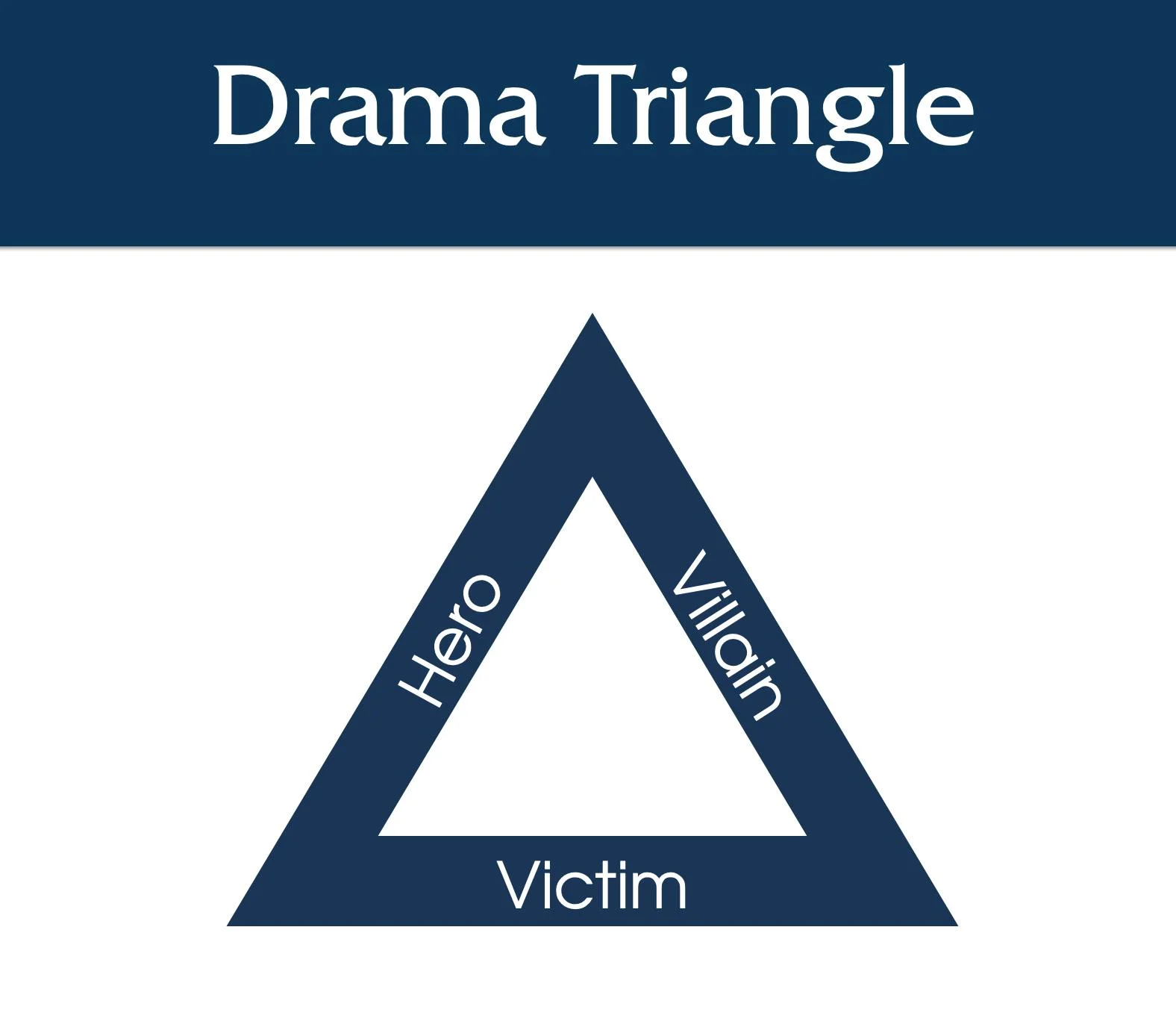

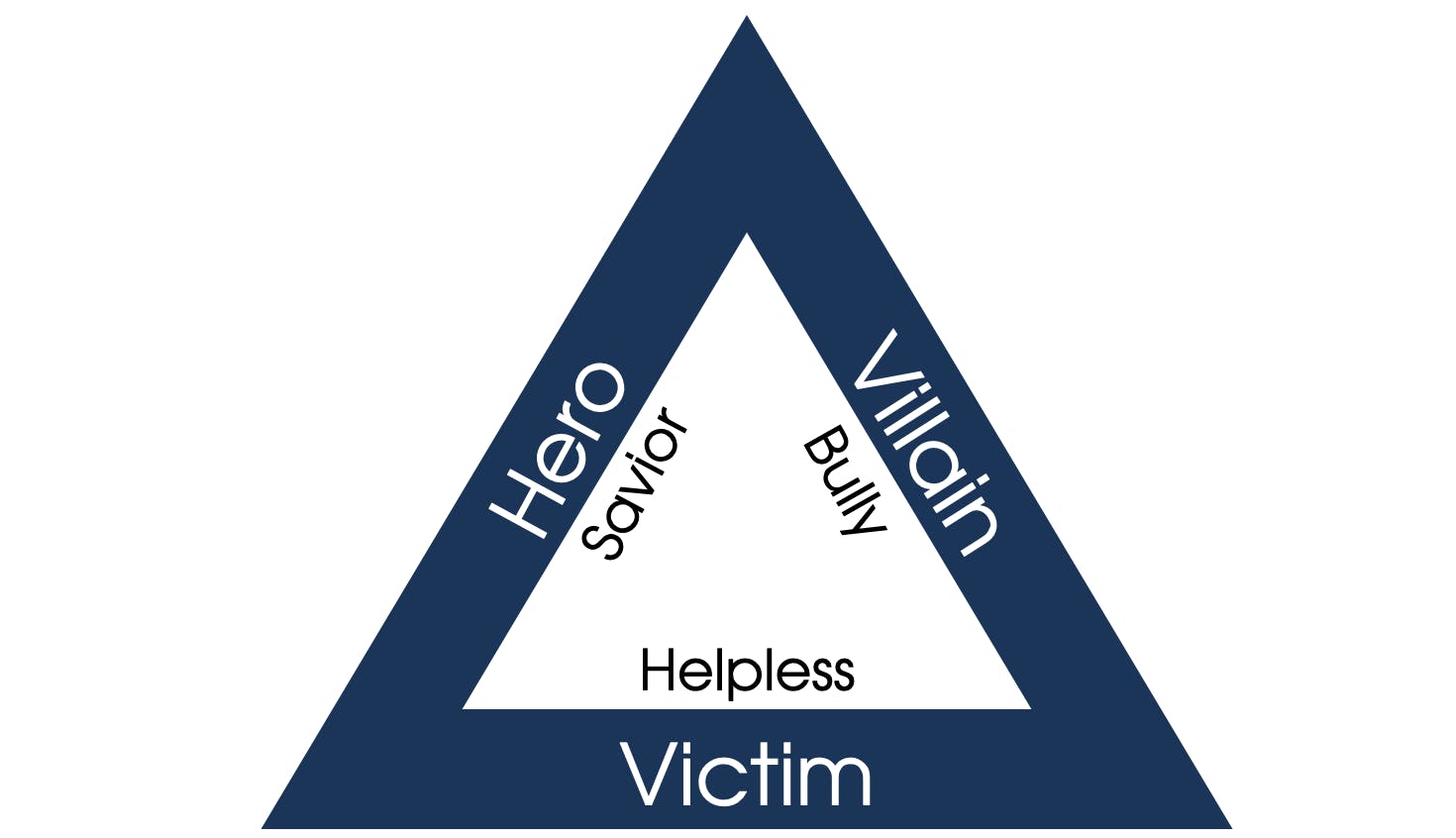

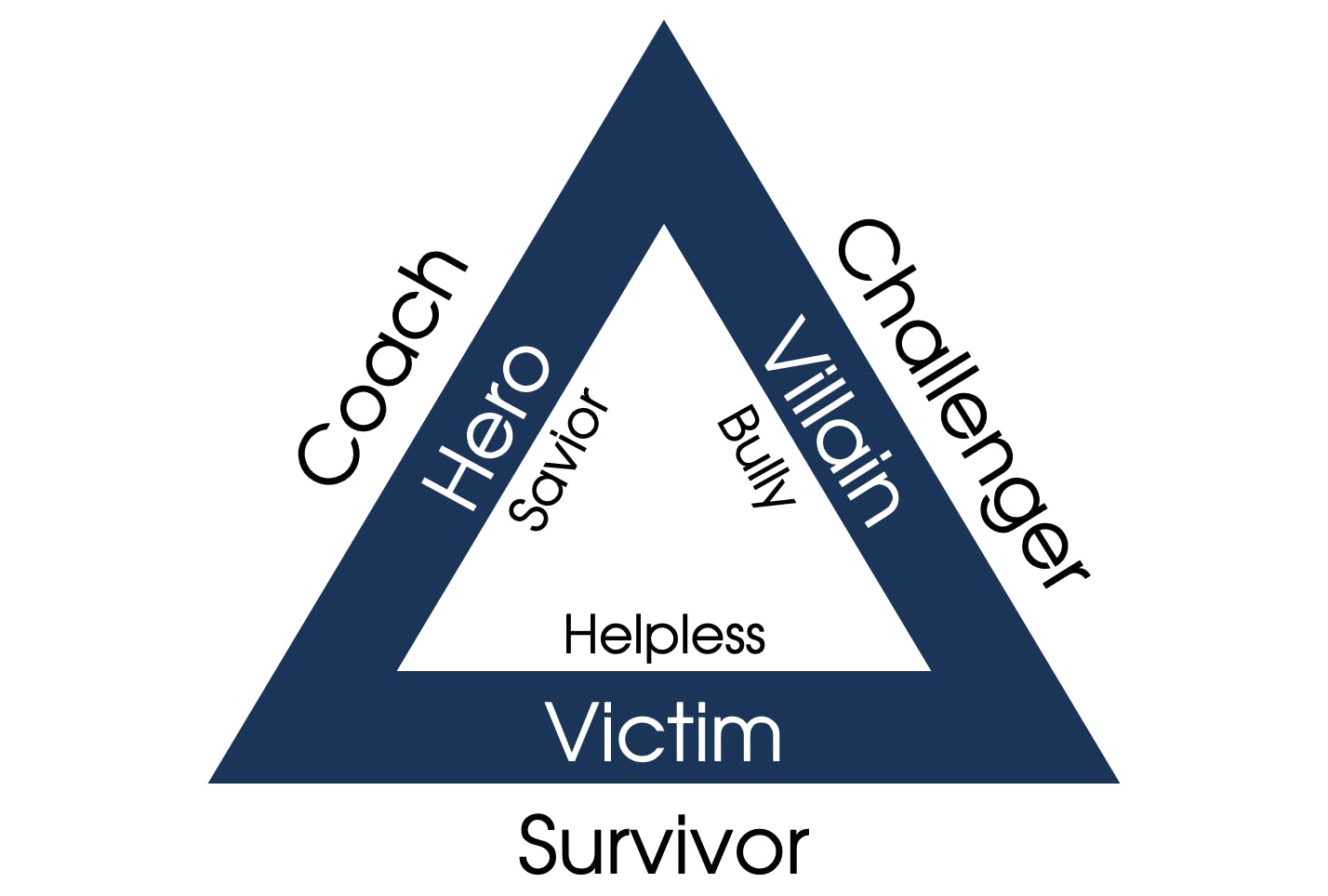

From a marketing perspective, I find this an interesting exercise that helps with copywriting. But I have a lot more to say about the Drama Triangle, from a theatrical perspective.

Villains are just confused heroes.

Villains and heroes are two sides of the same coin. They both can be strong, or weak; moral, or immoral, crooked, or straight. Villains can be rather heroic, when viewed from the right perspective.

I find melodrama boring, because the heroes and villains are too simple. The best villains are richly textured, and believe themselves to be the hero of the story.

One of the best heroes in fiction, in my opinion, is Magneto. He has moral justification for what he does. When he fights the X-Men, it is not because he hates what they are doing; he sees the X-Men as misguided, and continually tries to convert them to his cause. Magneto justifiably believes that mutants are being violently oppressed by humans, and the only way to secure the safety of his people is to aggressively attack those who threaten them.

Within every villain is a heroic and misguided urge to do good.

And the converse is: within every hero is a villain waiting to happen.

Every villain thinks themselves the hero; which means, every hero has reason to doubt themselves.

“Nobody is a villain in their own story. We’re all the heroes of our own stories.” – George RR Martin”

In the cowboy classic High Noon, Gary Cooper plays the sheriff of a town that is soon to be invaded by a criminal he locked up years before. He is not the stereotypical hero. He is a protagonist who is old, and bent, and misshapen; he is told by his community to leave town, and avoid a gunfight that could harm innocent people; he ignores them, and increases their danger by his actions; he even wears a black hat.

Frank Miller, coming back to town for revenge, wears a white hat. He is handsome and strong. His companions look like friendly frontiersmen that would sing you a song by the campfire. When this posse rides into town at high noon, these ‘villains’ are purposely portrayed at cross-purposes to their melodramatic stereotypes.

High Noon is a fascinating movie because it pushes against the edges of what we understand of heroes and villains. It confuses the audience, and forces you to ask: how can you tell the difference? If heroes can be weak and old and crooked, and villains can be strong and upright and morally just, how do you know who is who?

The only difference between a hero & villain is how they treat the victim.

Stephen Karpman was a psychologist who developed The Drama Triangle in 1968 for psychotherapy. These stereotypes help to identify others (and qualities within oneself) as opposed in this dynamic struggle.

“You either die a hero, or you live long enough to become the villain.” – Batman, The Dark Knight

A hero can be dark, and mean, and ugly, while villains can be smart, and pretty, and popular. They only true distinction is how they treat the victim.

A hero would sacrifice you, to save the world. A villain would sacrifice the world, to save you.

The best stories treat characters like a stem cell – they could grow either way. Like with Schrodinger’s Cat, which is both alive and dead until you open the box, every character in a story is both a hero and a villain, until they are faced with a dilemma involving a victim.

Derek Rucker, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School of Management, did some interesting research using Charactour, a database of 5500 fictional characters. He examined the results of 232,000 quizzes that revealed the characters people were most like, and most unlike. Surprisingly, there was an even distribution among heroes and villains.

When people were recommended other characters to follow, users did not prefer heroes over villains. Their use of the website encompassed heroes and villains equally. Stories are a safe way to explore villainy without actually hurting anyone.

“People have a preference for villains – unambiguously negative individuals – who are similar to themselves,” Rebecca Krause and Derek Rucker said in their research. Their study concluded that people were more likely to be attracted toward qualities that were similar to themselves, rather than repulsed from characteristics they don’t like.

The villain could be an alternate version of your customer

A villain can be instrumental in creating growth. People will identify with a villain that matches the characteristics of their lower self, when they are not who they want to be – can you use that perspective to move your character to grow?

If we take the villain of your customer journey, and identify it as the inciting incident that helps move things along, the villain can actually become your ally.

The villain for Sealy Mattresses is that crummy bed that gives you a backache. The villain for your car mechanic is that ominous sound in your engine. The villain for Snickers is your hangry mood. The hero, your customer, has to fight the villain, to protect the victim (their back, their car, their emotions).

The story you tell your customer about themselves has to be interesting, and the best stories are morally confusing. Just remember: you can only tell a hero from a villain by how they treat the victim.

So, rather than looking at your customer journey and asking, ‘Who is the villain in this story?’ a better diagnostic question could be, ‘Who is the victim in this story?’

Leave A Comment