People feel life is meaningless when they don’t have goals, rules, and feedback. (These are the 3 attributes of games, according to Dr Jason Fox, that I describe in-depth in my short ebook Gamify Your Work.)

Playing the game of life, and doing work that supports your lifestyle, is only made meaningful if we have goals to achieve, rules for how to play, and feedback on how we are doing. But how we play the game of life – and the criteria for how we win – will differ from person to person, from player to player. This means we evaluate the goals, rules, and feedback differently.

Your highest priority goal for your game might be financial success, emotional engagement, popularity, or physical comfort. Every player gets to decided which goal is the most valuable. I could rate financial success as the most important, while you could prefer physical comfort. This would lead to us playing the game of life differently – because we have different rules for how to win.

The game of life is something we all play, but how we play it is completely unique. In addition to having different goals, our skills and aptitudes are very different. The place where we start on the game board could be very different from other players, which creates a very different set of challenges in how we play. We can see this in the origin story of one of the world’s most popular board games.

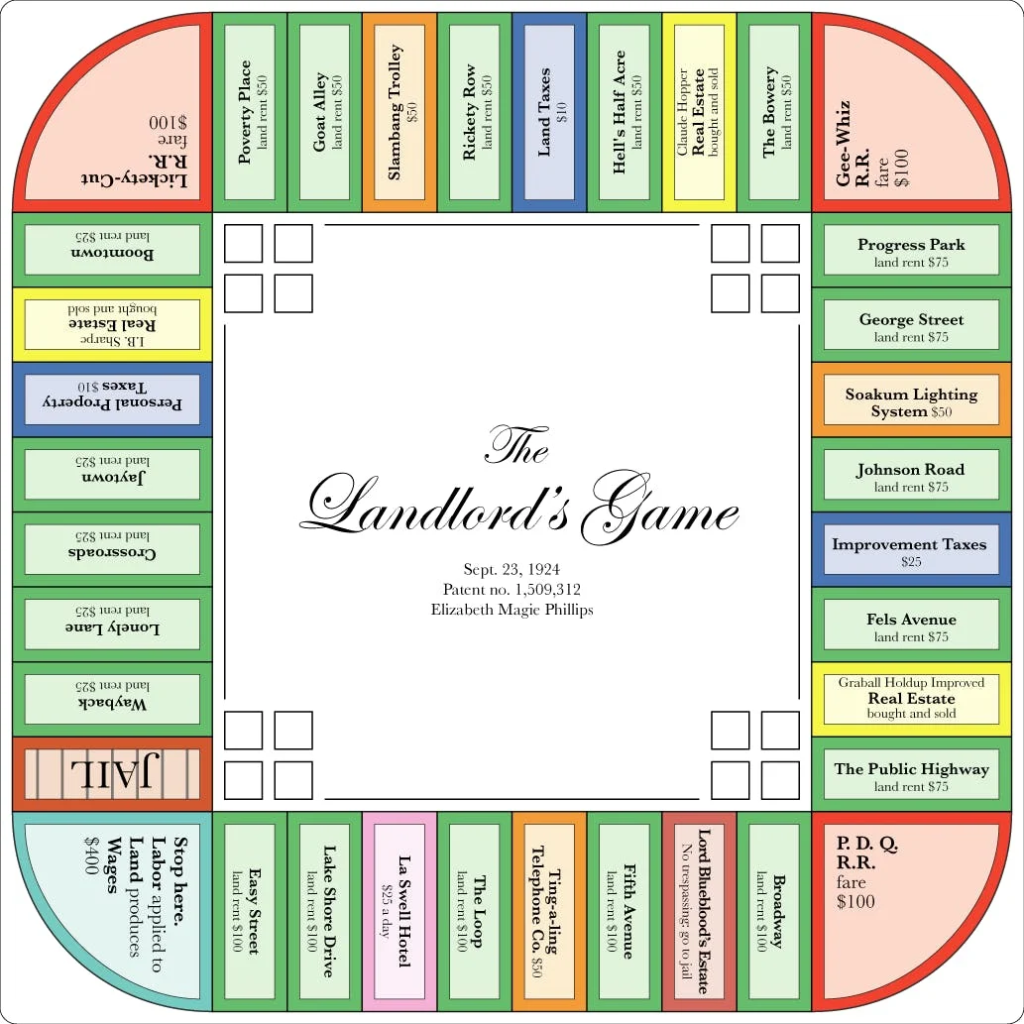

Monopoly was based on ‘The Landlord’s Game,’ which was originally published by Lizzie Magie (an anti-monopolist) in 1906. She created this game to demonstrate the negative consequences of single-tax theory.

Playing this game showed the players, experientially, the hazards of concentrating land in private monopolies. The lesson of this game is that future generations would be unable to participate in the economy, and a new aristocracy would be created.

Parker Brothers purchased the patent to the game in 1935, and tweaked it to make the friendly capitalist the hero. The goals of the game changed from ‘illustrate the flaws of capitalism’ to ‘train children to participate in the rigged game of capitalism.’

Do you see how changing the rules of the game can change the outcomes?

Why do we play the Game of Life?

If we were to agree on what the goals, rules, and feedback of life should be, they would probably involve nothing more than continuing to live. The rules are: breathe constantly; consume enough food and water to sustain your mortal form; sleep regularly for long periods; keep going. If you stop doing any of those things, you die, and the game is over.

Simple survival doesn’t seem to be the entire purpose of life, though.

You could make an evolutionary argument that the game of life is for procreation, and all of our living functions are designed to replicate ourselves. You could make a theological argument that the game of life is designed to assay our soul, so that we can earn a reward or a punishment after life is over.

However you view your game, it is your game. You get to decide the purpose, the boundaries, and the malleability of your game. Some people acquire their beliefs about their life early, and refuse to change it until the day they die. Some people modify the goals, rules, and feedback as they go, and change the purpose of their life over time.

Even though all humans playing the game of life are on the same metaphorical game board (living in a meatsuit on the planet Earth), the game that we play on this board is completely unique to us.

Different difficulty levels

Some of us play the game of life on hard mode, and some on easy mode. We choose the difficulty level that matches with our aptitudes and advantages, because everyone gets to decide what is prized in their game.

We also begin the game with different advantages. ‘Bloom where you are planted’ is advice that is nurturing to people who find themselves dealt a bad hand in the game, while ‘go where you are treated best’ is advice suitable for people with the privilege to stand up and leave one table and go to another.

If you believe that acceptance by your geographical community is the highest virtue, there are some lives that are better suited playing this game than others. If you happen to be born in a community of people who prize your features and your advantages, it will be easy to gain approval of those around you. But if you are born different than others, you will have a greater level of difficulty if you play this way. For people that like more challenge, a greater difficulty is preferable.

I once knew a black lesbian who lived in the South, a region of the United States of America that has many communities of people who are not friendly to blacks or to lesbians. She was fierce, and she loved playing the game of life this way. She was a champion for her community, very well educated, and enjoyed picking fights with bigots. Her game was going very well.

I also knew a mousy librarian who hated conflict. She came from a wealthy family, and prized silent contemplation above all else. I remember when she moved to the small college town where we both attended university. St John’s College used the Great Books Program, which meant there were no grades, and no tests. We read the great books of history and talked bout them. She liked the reading part, but not the talking part. I think she may have been agoraphobic.

She had a firm grasp of the material we studied, but in Seminar, the 3-hour long discussion sessions we had on Monday and Thursday nights, she was miserable. She didn’t like having her points rebutted, and often held back from contributing because she didn’t want to incite conflict.

Her difficulty level was different for reading and for talking. She read the books on easy mode; even though they were incredibly complex, she liked the challenge, and it suited her skills and deficiencies. But talking about the books was on hard mode. Others in the class had the opposite difficulty settings; reading was very hard, but discussing was very easy.

We all play the game of life differently, because we have different aptitudes. This means we have different ways to win. You can lean into greater difficulty if you like challenge, or lean away from it if you don’t.

Choose A Game You Can Win

Playing a financial game with a dirt spoon is very different than playing with a silver spoon. Games can be useful teaching tools to illustrate this (even when they are repurposed by your opponents). Monopoly is a perfect metaphor to describe the challenges with different difficulty levels in the game of life.

Imagine you are playing Monopoly, and all the other players start the game with $500. You begin with $50,000 and you already own a quarter of all of the properties on the board. Who will win this game?

Inheritance gives some people an asymmetrical advantage, if the goals of the game are financial. But by many other measurements of success – emotional connection, physical comfort, popularity, serenity, joy – winning could be easily attained by players who fail at finances.

This is why it’s so important to adjust your goals to your difficulty levels. If you have advantages in one area of your life, and disadvantages in another, you can choose to play the game that suits you best.

We need both success and challenge to enjoy playing. Set your goals in areas of your life where you are likely to attain success (and enjoy the challenge), and you will harness the momentum of victory to help you in those regions of the game of your life where success is not so certain.

Play to win what’s most important to you.

I want to invite you to look at the game of your life, at the difficulties and advantages you have, and the goals, rules, and feedback you have created for the different areas of your life. If you are dissatisfied with something, change the rules, prioritize different goals, and use the feedback that you have available to play the game of life the way that you want.

This article is an excerpt from my next book, Playful Productivity. To get notified when it’s ready, sign up for the wait list here.

Leave A Comment